Humanitarian

Vanuatu’s 2020 Humanitarian Emergencies and Women’s Experiences: Responses by the Vanuatu Women’s Centre

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by the Vanuatu Women’s Centre (VWC) and is based on discussions at a mini-retreat with VWC and Branch staff in July 2020, and mobile counselling reports from VWC and Branch staff to areas affected by the 2020 emergencies. The humanitarian response activities described in this report were funded by the following donors:

· VWC’s core national program is funded by the Australian Aid Program, including some of the humanitarian response activities described in this report.

· VWC is supported by UN Women funding from the Pacific Partnership to End Violence Against Women and Girls (Pacific Partnership) Programme, funded primarily by the European Union with targeted support from the Governments of Australia and New Zealand and cost-sharing with UN Women.

· Oxfam Vanuatu has recently become a funding partner and is providing support for activities in Malampa province, including VWC’s response to Tropical Cyclone Harold.

Introduction: The humanitarian context

A mini-retreat was planned by the Vanuatu Women’s Centre (VWC) for early July 2020, to provide an opportunity for staff to debrief and share their experiences from the three emergencies that faced Vanuatu during the first half of 2020.

This report summarises discussions at the July 2020 retreat, including VWC’s disaster response activities, what was learned about community experiences and women’s experiences, the challenges and trauma they confronted, and lessons learned. Some examples of women’s experiences are also drawn from VWC and branch mobile counselling reports.

This report focuses primarily on VWC’s response to Tropical Cyclone Harold and the ash fall in Tanna. It does not include a comprehensive analysis of the impacts of the COVID-19 state of emergency and its implications for women living with violence.

During the first few months of 2020, communities in Vanuatu experienced 3 humanitarian events:

· A national State of Emergency with curfew and social distancing requirements declared on 26th March to respond to the global COVID-19 pandemic, now extended to 31 December 2020. 1

· Tropical Cyclone Harold which severely impacted over 159,000 people across Sanma, Penama, Malampa and Torba provinces on 6th -7 th April, including shelter, potable water facilities, food sources, access to health services, educational institutions, and communications facilities, with a state of emergency declared to 9th August 2020. 2

· A widespread ash fall on Tanna island in Tafea province affecting 28,000 people in mid-April which resulted in food shortages, lack of potable water and the destruction of food crops, and which compounded the impacts of a months-long drought.3

These three events have had inter-connected, ongoing and severe impacts on affected communities, including the ability of women and children living with violence to access services and protection, and the ability of VWC and Branch staff to implement their planned activities. For example, VWC branch staff and their families in Sanma, Malampa and Penama provinces were directly affected by the impact of TC Harold with the need for homes to be repaired, and relatives needing shelter. Most members of VWC’s committees against violence against women (CAVAWs) in these provinces were also seriously affected, with one CAVAW member tragically losing her life during the cyclone while seeking shelter. The Penama Counselling Centre (PECC) office was located in one of the worst-hit areas, with two staff needing to use the office as a temporary evacuation centre for their families, despite the high risk of flooding, and the homes of all staff had damaged roofs, full of branches. In Santo, the Sanma Counselling Centre’s (SCC) Community Educator’s home had no roof, and the Project Officer’s home was also damaged.

For almost a week following the cyclone, VWC was challenged with communicating with several Branches due to extensive damage to the telecommunications network. With concerns for PeCC staff, on one of the most severely hit islands, VWC sent its Finance Officer to Pentecost on 15 April to communicate with staff and assess the situation.

1 Vanuatu Ministry of Health COVID-19 Updates – COVID-19 (gov.vu)

2 https://ndmo.gov.vu/tropical-cyclone-harold/category/99-situation-update-infograph;

and https://covid19.gov.vu/index.php/updates/soe

Despite the severe disruption to their personal lives and damage to their own homes, Branch staff returned to work a day or so after the cyclone, to restart their essential services and conduct assessments. As phone contact was re-established, contact with CAVAW members in affected areas enabled VWC to understand the cyclone’s impacts in these areas and provide moral and other support to CAVAWs.

VWC held an emergency planning meeting in Port Vila with Branch Project Officers in April 2020 soon after TC Harold, to identify immediate needs, how VWC and Branch staff could best respond, and to re-focus planned activities in the coming months. Ongoing COVID-19 restrictions meant that VWC was unable to hold public meetings or workshops in communities to raise awareness of violence against women and children (VAWC) and its impacts, or planned training workshops to help prevent it. At the time TC Harold struck, counselling activities were largely taking place by phone.

VWC’s emergency response activities: mobile counselling and relief distribution

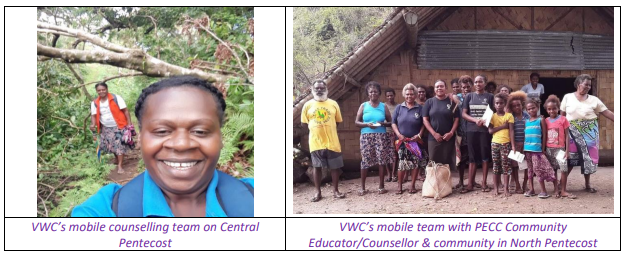

At VWC’s April 2020 planning meeting, VWC and the branches scheduled a series of mobile counselling activities in locations affected by TC Harold and the Tanna ashfall. Two mobile counselling teams were sent from VWC’s Port Vila counselling section to Central and North Pentecost. Language barriers and staff capacity were raised as a challenge by PECC staff, with many Pentecost island communities unable to understand or communicate well in Bislama. To deal with this issue, each VWC mobile counselling team had staff able to speak local languages, and one team from the Sanma Counselling Centre (SCC) also assisted. Both VWC teams left Port Vila a fortnight after TC Harold: the first team spent one month on Pentecost and the second was there for almost 3 weeks, accompanied by the PECC Community Educator/Counsellor. Both VWC teams visited around 50 different locations across more than 13 wards.

SCC and the Malampa Counselling Centre (MCC) also began to respond immediately after the April planning meeting. SCC visited 20 locations from April to June on Malo, Aore and Tutuba islands, the west coast of Santo, and South and Southeast Santo such as Fanafo, Banban, Sarete, Stonehill and Vunavos, as well as Nduindui on Ambae, and Central Pentecost in Penama Province. During May and June, MCC visited 19 communities in Malampa province on Ambym, Paama and Malekula, including Potvoro, Tenmaru, Metkun, Leviamp, Tisman. The Tafea Counselling Centre (TCC) visited 5 locations affected by the ash fall on Tanna, including Lonau, Waisisi, Lapangtaua, Lenamau, and Ianaluqenian.

_________________________________________________________________________________

In total, 100 awareness-raising/prevention sessions were held with 4740 people in response to TC Harold and the Tanna ash fall and most of these also covered COVID-19; 2827 women, 673 men, 727 girls and 513 boys attended these sessions in Penama, Sanma, Malampa and Tafea provinces.4

The first day of mobile counselling usually begins with a day of community awareness/prevention public talks on violence against women and children, with various stakeholders such as male advocates, police and local leaders involved, as well as VWC and Branch staff and CAVAWs; this is usually followed by a further 2 days where VWC and Branch staff remain in the community to respond to women’s, men’s and children’s requests for further information, and to provide counselling to victims/survivors in a safe and accessible place for women who often cannot afford to travel to the centre. Instead of having a large public gathering or series of age-targeted community awareness events on the first day of mobile counselling, staff needed to innovate with different ways of making contact due to the COVID-19 state of emergency restrictions – including by setting

4 This does not include the preliminary assessments undertaken in collaboration with NDMO or other agencies.

up tables/tents that enable small groups and individuals to come to them to collect information and receive the help they now needed more than ever. All affected Branches coincided mobile counselling visits with National Women’s Day celebrations in mid-May, providing some cyclone-affected communities with a much-needed morale boost.

Over 2-3 days, awareness sessions were held in communities on VWC services and domestic violence during disasters and COVID-19. Information, education and communication (IEC) materials were distributed with the 24-hour counselling phone number for VWC. Where needed, clients were referred to VWC for further support. Women’s stories of their leadership, achievements, hardships and experiences of violence during the cyclone were documented. Awareness sessions were often held in tents or makeshift temporary shelters, as community spaces had often been destroyed. This was particularly challenging during rainy periods.

Travelling from one community to the next sometimes required long walks by VWC and branch staff over difficult terrain, since many roads were still water damaged with trees blocking the way. Community members helped to carry the supplies. Boat journeys were also needed in rough seas and truck journeys over very rough tracks. Life jackets were not always available, as some boat drivers do not have them. Although VWC and branch staff are used to travelling in very remote areas in difficult conditions, this was a new level of challenge which was frightening at times for the team members, and it brought home to all how very tough it has been for all community members in the response and recovery phase of TC Harold.

Accommodation was also very challenging for staff in all locations, including on Tanna. In cycloneaffected areas, staff stayed in community halls (in their tents) when these were still standing, and in churches. When community members’ houses were still standing and safe, they offered staff to stay – since it is well known in Vanuatu to invite strangers into your house without a second thought.

VWC and branch staff were also involved in Gender and Protection cluster meetings and some staff assisted with initial assessments in collaboration with the National Disaster Management Office (NDMO) and other relief agencies. These initial assessments helped VWC and Branches identify the most affected areas and the immediate needs of the communities. For example, after participating in an early assessment organised by another agency in one province – where a team entered a community late in the day, with no relief supplies to distribute, and with people waiting most of the day with some expectation of practical help – it was clear that mobile counselling teams needed to equip themselves with water, food and other relief supplies when visiting communities.

To assist with some immediate relief, VWC and Branch staff provided portions of rice and other basic food, dignity kits provided by UNFPA (provided for SCC’s mobile counselling), and water to each household in visited communities. In some visits, VWC coordinated with the Red Cross to distribute second hand clothing. After visiting some communities, SCC heard that many women and girls had no underwear, and this was added to the bags distributed to each household. A women’s representative in each community worked with the Chair of the Community Disaster and Climate Change Committees to organise distributions and ensure fair distribution among households and the various faith denominations.

VWC’s experience with responding to previous disasters – particularly Tropical Cyclone Pam and the long-term eruption and ash fall from the Lobenben volcano on Ambae island and evacuations – meant that VWC had already developed considerable expertise at bringing a gender lens to disaster response, and already had leaflets focused on the links between violence against women and disasters. These resources were quickly reprinted to take into communities, along with a new leaflet on COVID-19, the Gender and Protection cluster’s card on domestic violence (which provides details 7 on how to contact VWC) and various other resources that are used in VWC’s ongoing community awareness-raising, violence prevention and training activities – such as posters and leaflets on the Family Protection Act, stickers on the 8 rules for children’s safety, and the VWC brochure.

VWC also needed to provide for its own staff to be safe and dry during the mobile counselling visits, to ensure that they did not pose an additional burden on communities struggling with their responses to the disaster in the early weeks following TC Harold. VWC and Branch teams were provided with tents, tarpaulins, and solar lights.

VWC’s Humanitarian Officer participated in both the rapid and deep assessments undertaken by NDMO with the Gender and Protection Cluster. In the immediate aftermath of TC Harold, there were some challenges associated with these assessments. Team members were not provided with adequate training on how to use the assessment tool, and there was inadequate debriefing following the visits. Travel by boat was required in some areas, but life jackets and other safety equipment were not readily available.

Community experiences and responses

VWC and branch staff have extensive experience with planning mobile counselling in communities and they knew what was expected from them and what to do to make the visits as effective as possible. Staff were able to build on good working relationships with government agencies, other NGOs, provincial government staff, chiefs, church and women leaders. VWC has established a strong network of CAVAWs and male advocates, many of whom are community leaders. These supporters assisted VWC to organise the mobile counselling in their communities and accompanied them where they could. The visits were arranged through chiefs, church leaders, area secretaries, community disaster committees, CAVAWs or male advocates, some of whom are also chiefs or police officers.

Most communities were aware of the mobile counselling visits, and had prepared for the arrival of VWC and branch staff. Organising travel was sometimes very difficult, with poor or no phone connections during the visits to communities affected by TC Harold. All communities were appreciative of the practical support through relief supplies provided by VWC. All the communities expected and hoped that the teams would be bringing food, which was in short supply everywhere.

In Tanna, people living in the areas affected by the ash fall were struggling to find food and water. Many women said that they were skipping meals and baths to save water and food for their children, to make sure that there was food for the next meal or day. The ash fall had destroyed water holes and houses and most of the crops and other vegetation were also destroyed. Nuts and coconuts were used as food for those who did not have enough to sustain them until the next meal. Women had to cover their head and body to avoid skin irritation while preparing food for their families. Families had exchanged traditional mats and carvings with people from other areas in Tanna for crops to plant, but the continuous ash fall had killed all these new crops. Women were trying to find ways to get money by selling traditional mats and animals at the market, so that they could buy canned food and rice, but it was very expensive to pay for transport to the market. In some areas, women had come together to weave traditional mats to support their families and buy food.

Many issues were identified by community members affected by TC Harold with many harrowing stories of survival, and many near-death stories. Although the majority of people who came to listen to and talk to the mobile counselling teams were women and children, men were also interested and also attended the public talks, as well as some disabled people. Staff listened to their stories of narrow escape, and heard the fear they had all experienced. Most of the counselling provided – in small groups and one-to-one – was trauma counselling, but some counselling was for instances of

violence against women. Houses were destroyed, along with gardens, and cash crops such as kava and coconut. People’s belongings were scattered everywhere or covered by collapsed houses, and some women had to collect belongings such as clothes and traditional mats hanging from trees a long distance away from their homes.

Lack of clean water was a common problem facing most communities. For example in Malekula, water used for cooking was contaminated by mud and some people had diarrhoea as a result, as they had no other choice than to use this for cooking and drinking. People who lived inland faced difficulties finding water to wash their clothes and themselves. Similarly, water on Pentecost and Sanma was often contaminated by debris, but was the only available source for people to use. On Pentecost VWC staff found that women were avoiding washing due to the distance they needed to travel.

Extracts from VWC mobile counselling reports from Pentecost

Most women changed immediately into the clothes that we distributed while others waited until they could take a bath. Wet and dirty clothes were piled up, with no clean water for washing. Most families lost many essential household items such as pots and pans, dishes, plates, beddings and mattresses.

In one village, only 3 houses were still standing, and the rest were all destroyed and had fallen down. The majority of houses across 11 wards have been destroyed.

There were difficulties in finding transport and communications as roads were closed due to fallen trees and communication towers had also been destroyed. People hardly had baths. The women have to walk about 30 minutes to the nearest water tap to get access to clean water.

Kava crops had been badly destroyed along with food crops in gardens such as banana, taro and island cabbage, the main foods used in everyday meals on the island. Coconut trees were badly damaged and it will take years for new ones to grow again. Building materials such as bamboo and natangura were destroyed.

Bathrooms and toilets were all carried away by the wind and people are using bush toilets which are unsafe and unhygienic. As Pentecost is well known for its traditional red-mats, commonly used in ceremonies, women grieved as baskets of mats were blown away by the powerful winds. These mats are estimated to be 7000vt per mat. Cash crops have all been destroyed. It will take years for crops to grow and for plants and building materials to flourish again.

A lot of questions were asked about COVID-19. There were reports of domestic violence especially emotional, financial and physical violence. We think there will be a lot of domestic violence during the recovery phase, especially now that people are still living in temporary evacuation centres with other families, and with kava, cash crops, food gardens and livestock all being destroyed.

Communities were very welcoming of the mobile counselling teams. Community leaders arranged and assisted with transporting relief materials to the distribution areas. In some places CAVAWs helped with the distribution of relief supplies, and in others community members assisted too. In some areas in Santo and Malo, Area Secretaries accompanied staff in the communities. However, VWC and branch staff were always in charge of the distribution, because it was observed in a few areas that the distribution of supplies from other agencies had been unfair, and in some cases people complained that they had been used to pursue political interests.9 Many villages visited after TC Harold were places where VWC and the Branches had never been before, and some were places where community leaders had previously refused to allow a mobile counselling or community awareness visit.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Many community members are still living with the trauma of the TC Harold – extracts from mobile counselling reports from Penama and Sanma provinces

VWC and branch mobile counselling reports document many examples of the trauma experienced by community members, which were shared with staff while visiting communities.

· During the night of the storm, the women told the men to prepare. The women gathered the children and they all hid in a nakamal close to the sea. The men were busy in the nakamal drinking kava. The sea waves came and swept a little boy of 6 years old outside. He was saved by being caught up in the roots of a pandanus tree.

· Powerful winds ripped clothes off the bodies of some women and even tore their clothes apart. One woman who managed to save her clothing shared it with others in her village to keep them warm, but most of the children were naked in this community.

· A young boy saved his sister, mother and grandmother by blocking them with only a sheet of plywood, while he had to lean against the plywood in the storm so it wouldn’t fly off.

· Women, men and children took shelter in a hollow tree trunk. The winds shook the tree vigorously so they ran and hid next to a fallen wall of a house and took shelter there until the storm went down.

· A CAVAW member was killed during the storm when a concrete block fell on her where she was sheltering. Her husband had some bruises and cuts from shattered and broken timber and glass. · A man emptied his water tank and lowered women, children and babies inside to take shelter from the storm.

· Women cried as baskets and mats weaved for custom ceremonies and sale were all blown away in the wind.

· More than 50 people on Tutuba Island were saved by sheltering under a rock, less than 5 metres long and 3 metres wide. A grandmother assisted a young women with a very young baby (less than one month old) to get to shelter. The grandmother covered the baby with 3 blankets; after 6 hours, the grandmother unwrapped the baby, to find him weak and unconscious, but still breathing. It took several minutes for the baby to regain consciousness and begin to feed again.

· One woman had to wake her husband after the storm stuck, and by the time he woke, their kitchen had blown away. They ran to the mother-in-law’s house, the strongest house they knew, and it had also disappeared. When she looked around, her husband and two children had disappeared. She grabbed a piece of firewood from the mother-in-law’s old fire, and placed it on her breast to warm herself, but it was still on fire and burnt her badly. Later she discovered where her husband, her 2 year-old daughter and 8-month old baby boy were sheltering. The girl could not talk, and both were very weak. She is doing her best to make them happy again, and her husband is trying to rebuild their house now.

Women’s and girls’ experiences and gender equality issues

In Tafea province, staff observed what they already knew: that women are the managers of household affairs, and this was highlighted even more during the impact of the ash fall disaster. Not only were they working to provide and care for their families, they were also supporting each other to get through the difficult time. People in communities depend entirely on food they plant from their gardens and the cash crops that they have – most have no paid jobs, so they depend entirely on what they have grown to eat and make money from. During and after the ashfall women suffered: they worried about food as everything was destroyed, so their means of earning funds were destroyed; the shortages in everything resulted in high tensions within families and communities, and arguments were common.

All the communities visited following TC Harold were very busy rebuilding, and women were spending most of their time cleaning up and doing other essential activities. Staff were often helping alongside the women – this was the best way to spend time with women, hear their stories and experiences and provide trauma counselling.

Staff noticed that in some areas tarpaulins provided by other agencies were used to cover trucks or kava bars, while women struggled to find proper shelter for bathrooms and toilets. Toilets and bathrooms were destroyed and women and girls were challenged to find private and safe ways to shelter them while bathing and going to the toilet.

In all communities, staff observed that women were the ones trying hardest to rebuild after the destruction, although many men and children were also rebuilding and helping to replant. For example, in Penama province, staff noted that women had so much to do that it was challenging to do mobile counselling. Some communities had to attend funeral ceremonies and women were required in the nakamal to prepare food. Women from North Pentecost communities told VWC and PECC staff that they needed more awareness-raising on everything about violence against women and girls. They mentioned the need for good water supply system, health facilities and for a Police post so that women can get the help they need when they are confronted with violence.

In Malampa province, many women shared their trauma from living through the cyclone and the challenges they faced in its aftermath, as well as their fears about the COVID-19 state of emergency. They were happy to receive VWC’s flyers with information on COVID-19, since most communities had not received any reliable information or awareness-raising about the pandemic and what to do to prevent the spread of the virus. MCC counsellors reported that women have gone through emotional, physical, financial and sexual violence after TC Harold and during the COVID-19 state of emergency as these events raised many issues and challenges. Women asked for information and raised their concerns about the home school package: many felt that they are not educated enough to support their child, and those with more education also had difficulties accessing the resources needed to support their children with their studies. For example, they could not afford to pay for the daily mobile data needed to implement the home school package, and some felt victimised if the child’s home package was not completed. Most men did not assist women with the home schooling. VWC’s humanitarian response officer also witnessed chaos for women after the cyclone, with many women leading the work to rebuild, replant and clean up, while still taking care of the elderly, those living with disabilities, children and pregnant women. She reported that there were many places where evacuation centres or available safe spaces were not available to cater for the most vulnerable community members during and after disasters, and this was also observed by mobile counselling teams in Penama and Sanma provinces.

In every area visited by mobile counselling teams, staff noted that there is need for health facilities to be provided for women to avoid women travelling very long distances when they need health care, including when they suffer from violence. In many places, even those clinics that do exist were damaged. Women said that they needed to access health facilities – particularly those with sick children, those caring for the elderly and pregnant women – but very poor road conditions and high cost make this even more difficult, along with the loss of many boats due to the cyclone. People who need to get to the sea, shop owners, and vendors also could not travel to their destinations to earn their living.

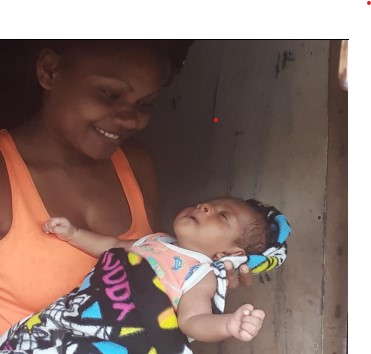

Babies born during the cyclone: extracts from mobile counselling reports

- young mother shared her experience giving birth during the cyclone. She had to deliver her baby girl outside (in the wind and rain), while other villagers crowded in the nakamal to keep safe from the winds. The women had to hold up pieces of cloth (lava-lava) and plastic sheets to completely block her so others won’t look while she was in labour. The baby was born and is in perfect health.

- In another village, women had to rush the mother and newborn baby during the storm to a nurse practitioner’s house to have the umbilical cord and placenta cut off.

- Three newborn babies were wrapped in plastic bags with an opening around their face to be able to breathe and suck from their mother and keep them dry.

Photo: Mother and the Baby

Haroldton was born immediately after the cyclone passed, assisted by a village nurse, who needed help to get over and under trees to the mother’s home. Fortunately, the family still had a new razor blade to cut the umbilical cord. After 5 days they were finally able to get to the hospital for a check-up, and both are healthy

Women threatened and chased while trying to find water – extract from Sanma Counselling Centre mobile counselling report

There was no water supply in Luganville area for 6 days, until the pump station was able to get electricity again. A few people had water tanks and wells, and were lucky to be able to wash and cook. For those with no rainwater, some used dirty spring water near their communities. Women from one community had to walk to fetch spring water from an area near the coast. Young men threatened them, saying that they were the landowners, and chased them with bush knives. They told them that Sunday was not the day for collecting water or fishing.

One huge concern in all areas during the pandemic and after the cyclone was the closing down of vegetable markets. Women market vendors are usually the ones in the family who raise and provide the funds for school fees and other needs, but this source of support disappeared overnight with potential long-term consequences for children and families. The street sale of cooked food (known as “20 vatu”) was also prohibited.

In Sanma, women were particularly worried about shelter in the coming months, food, education, and finance. They had nothing left – everything was destroyed by the cyclone, and they continue to live in very poor conditions. For example, when the Sanma team visited Tutuba Island, all the villagers were still living in caves, and in Aore people were living under tarpaulins.

Two stories of domestic violence from cyclone-affected areas

Clara had lived through domestic violence for many years. However somehow she was very strong when TC Harold struck. After the cyclone, her house was lost and she was worried, and she loudly asked her husband to rush to make them a shelter to sleep in, but her husband smacked her left leg with a big knife. She couldn’t walk for one week and a half. Her son in law helped her to fix a temporary shelter for the family to live in.

Maria is 35 years old and has 5 children. After the awareness talk during the mobile counselling, she told the counsellor that she now realised she had been through financial violence throughout her marriage. Every time she made money for the family, her husband took it all and just used it on kava or cigarettes. There was nothing left for her or her children. When the team arrived, the children had no clothes. Before TC Harold, the family worked together to cover their thatched roof and tie down their house with rocks. But the wind took everything, including the kitchen, and they only had one sack of copra each to cover themselves with. Maria was very scared during the cyclone but could not show this to her children, because her husband and the children were all crying with fear. She realised this was another challenge she had to face in her family. During the cyclone her husband apologised to her, and even during the storm, it made her laugh a little bit. After hearing SCC’s information, she wonders if he was apologising for always taking her money.

Conclusions, lessons learned and recommendations to other agencies

The visibility of the VWC Network of branches across cyclone-affected areas, and especially in isolated communities, has helped build respect for and the status of VWC as an organisation that communities can rely on, especially in difficult times. This has been important for strengthening relationships with communities – and for establishing new relationships in many cases where VWCs work has previously been rejected, particularly in Pentecost. The efforts undertaken by VWC are a sound building block for future collaboration on the prevention of violence against women and children, and for appropriate response to victims/survivors, during the rehabilitation and in future disasters. Several villages that were visited for the very first time have already requested follow-up visits from branches, including on Pentecost.

It was distressing for Branch staff in one province to join an assessment team organised by another agency, where no basic provisions were taken into the community, and where community members had waited for many hours, hoping for some practical help from the team. VWC learned from this other agency’s first response and ensured that some food, water and provisions were taken on all mobile counselling visits. In some areas, staff observed that relief supplies from other agencies had been distributed unfairly to further political or other interests, and women from some communities also mentioned this. For example, in one area, widows only received half of the rice ration provided by other agencies, regardless of their need. This is a risk that all agencies need to be continually aware of in responding to all emergencies.

1. All first responders in disaster situations need to go into communities prepared to offer practical relief for community members, and particularly for women responsible for feeding their families.

2. VWC staff will continue to have full control over the distribution of VWC’s limited relief supplies to ensure fair distribution during mobile counselling when responding to disasters, and during every stage of the response and recovery.

3. The need for refresher training on assessment tools could be assessed and considered by first responder agencies, before sending assessment teams to future disaster sites.

Safety of staff needs to be given priority in all future mobile counselling efforts, and life jackets must always be provided, since their availability cannot be relied upon. This was also raised as a concern when VWC and Branch staff participated in response and assessment visits organised by other agencies.

4. All teams organised by VWC, and those undertaken in collaboration with and organised by other agencies, need to take adequate protective equipment for assessment team members, including life jackets and other basic provisions.

Women and communities in general are still living with the effects and aftermath of TC Harold and the ash fall on Tanna. These impacts are summarised below.

Summary of issues raised during the mobile counselling

· Deaths caused by injuries during the cyclone evacuation (Malo, Central and South Pentecost).

· Reports of domestic violence – especially emotional, financial and physical violence – and concerns about further escalation during the recovery phase as stress from cramped living conditions and the loss of livelihoods may trigger more violence, in situations where it remains very difficult for women to seek help due to poor transport and access to other communication means, and lack of funds.

· Widespread destruction of homes, resulting in a lack of secure housing/shelter and the need for families to be accommodated in temporary shelter or evacuation centres.

· Insufficient safe houses or evacuation centres in communities, with stories of evacuees in risky situations during the cyclone (e.g. hiding under tables, in water tanks, in hollow tree trunks and in livestock enclosures, babies being wrapped in plastic bags with breathing holes cut out) and up to five families currently living together in cramped situations.

· Poor awareness among communities on cyclone preparedness measures.

· Insufficient privacy, protection and hygiene of toilets (including from rain).

· Lack of access to clean water, including water for drinking, cooking and bathing.

· Difficulties faced by families during and after the storm for those living with disabilities.

· Trauma among survivors of the cyclone, especially children.

· Lack of access to health facilities due to poor road conditions after the cyclone, and insufficient medical supplies at clinics.

· Lack of underwear and clothing for women and children.

· Immediate food needs and long-term food security and livelihood concerns due to damage to gardens (yam, banana, manioc, taro, island cabbage) and cash crops (e.g. kava, coconut/copra) and inaccessibility of gardens due to fallen trees and debris, especially for elderly women.

· Lack of access to natural and traditional building materials due to the destruction of bamboo and natangura.

· Loss of assets during the cyclone, including red mats (Pentecost) and livestock, kitchen utensils, bedding and mattresses.

· Increased challenges in women’s and girls’ domestic care work due to the loss of kitchen utensils and additional time/labour to collect clean water located further away.

· Difficulties in finding transport and communications as roads were closed due to fallen trees and communication towers had been destroyed.

· Women’s concerns about relief supplies from some agencies being unfairly distributed.