4. Methodology

4.1 Aims of the research

The original aim of this research was to establish a baseline of the number of young women and girls who access VWC’s counselling service in Port Vila, to assess how well VWC’s outreach is extending to this high priority group. To this end, July 2015 – June 2016 was chosen as the year of study, so that a comparison could be made with a future year.[i]

| Primary prevention aims to prevent violence before it occurs by: – addressing the cause of violence (gender inequality), and – enhancing the factors that protect women from violence. Secondary prevention includes responding to violence, early intervention with individuals at high risk, and preventing further violence. |

However, as the research proceeded, it was clear that an accurate “baseline” would be very much earlier in VWC’s history. While VWC has always focused on women and girls of all ages, the findings from the national prevalence survey in 2009 prompted VWC to immediately redouble its efforts to reach out to both young women and men.

VWC’s focus on outreach to young people was further intensified following an internal review of strategies. This was incorporated into VWC’s 5-year program design commencing in July 2016. The aim was to increase the targeting of youth nationally in VWC’s efforts to prevent violence before it occurs, and to respond to violence by reducing the likelihood of repeated incidents involving young women and girls (primary and secondary prevention).[ii]

Following a pilot study of VWC’s Port Vila database, the scope of this research was extended to include quantitative data from all Branches that were operating during 2015/2016, to provide national insights.

The scope was also expanded to review qualitative data collected from 2016 to 2019, to assist with analysis of quantitative data by providing insight into the daily lives of young women and girls living with violence. The age of clients was available from July 2016 in the qualitative database collected through VWC’s ongoing monitoring, evaluation and learning work.

Box 6: Research questions

The research process aimed to answer the following key research questions:

- What proportion of VWC Network clients are young women and girls?

- What types of issues are young women and girls seeking help with from the VWC Network?

- What have we learned about the experiences of young women and girls?

- What have we learned about how young women and girls come to know about VWC’s services, and what prevents them from seeking help?

4.2 Data collection and analysis process

4.2.1 Quantitative database

VWC has collected quantitative weekly and monthly data on services provided to clients since its establishment. These data are collated annually and disaggregated by the following categories:

- new cases and repeat counselling sessions;

- location – VWC, branches and CAVAWs;

- sex and age – adult women, and girls and boys under 18 years;

- the delivery mode of counselling – centre-based, phone, and mobile counselling in urban settlements, rural areas and outer islands; and

- the type of violence/issue that clients are seeking help with – domestic violence (DV), child maintenance (CM), family maintenance (FM), child abuse (CA, further disaggregated by physical and sexual abuse), rape, sexual harassment (SH), incest, and others; and

- clients living with disabilities – VWC began trialling how to record this in 2015/2016, but this data was not systematically collected until July 2016, and consequently has not been recorded in the database for this study.

Client files record the date of birth of each new client, and their current age is recorded on weekly sheets for both new clients and repeat counselling sessions. A separate weekly data sheet is compiled by each Counsellor, and collated into monthly process reports by Branch Project Officers and the VWC Counsellor Supervisor/Manager. This data is checked and collated by the VWC Research Officer, and compiled 6-monthly into progress reports to the funding agency. At the end of each funding phase, data is collated into an Activity Completion Report, which provides a summary of clients seen nationally. However, due to the large quantity of disaggregated data collected and collated, age breakdowns (other than adult and child) are not collated on monthly data collection forms, and therefore not included in 6-monthly progress or Activity Completion reports.

For this research project, quantitative data was extracted on the age of clients from the VWC and branch counsellor weekly sheets for the twelve months from July 2015 through to June 2016. VWC’s definition of a child is a boy or girl under 18 years. For the purposes of this research, young women are defined as those aged 18 to 29. The data included in Annex 1 is disaggregated as follows:

- Girls under 18 years

- Young women aged 18 to 24

- Young women aged 25 to 29

- Women over 30 years

| Definitions used in this research: ▪ child – under 18 years ▪ young woman – aged between 18 and 29 |

VWC also provides counselling to boys under 18, but for the purposes of this research, data has only been extracted on girls (0-17 years).[iii] Age breakdowns for young women (18-24, and 25-29) were selected because they facilitate comparison with VWC’s national prevalence research (see section 3).

Quantitative data for this research was extracted from VWC in Port Vila and the branches. Although CAVAWs are trained to record disaggregated data for counselling on all the indicators listed above, the capacity to collect, store and accurately report disaggregated data on age varies considerably in remote areas of Vanuatu. Consequently, CAVAW data was not included in this study. Nor was data from PECC, since the Penama branch was established in January 2017.

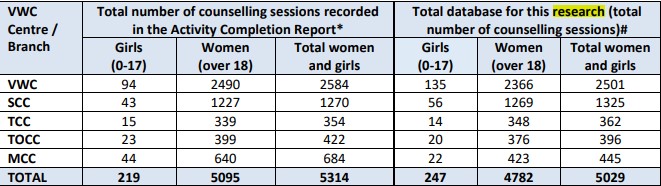

The total database for this research was 5029 counselling sessions, including 4782 with women and 247 with girls under 18 (Box 7); this includes new clients and follow-up counselling sessions. During the data collection process, it was found that age was not recorded on weekly sheets for 495 counselling sessions with women and girls (9% of the total counselling sessions undertaken). A systematic process was used to search for this missing age data, including by asking the counsellors concerned to check the client files and update the weekly sheets as needed. This process significantly reduced the number of counselling sessions where age data was missing to 285 (5% of the total sample). It also showed that there were 28 more girls under 18 who participated in counselling sessions than was originally recorded in the Activity Completion Report (Box 7); these girls were incorrectly recorded as young women over 18 (the most likely reason for this is because they already had children).

Box 7: Database of total counselling sessions by location, July 2015 – June 2016

The qualitative database includes all case studies related to young women and girls documented by VWC and Branch staff from July 2016 through to May 2019.

4.2.2 Qualitative database

The case studies included in the qualitative database were not identified or collected specifically for this research. Like the quantitative data described above, they are drawn from VWC’s internal monitoring and evaluation database.

VWC’s monitoring and evaluation plan includes several qualitative indicators designed to assist with monitoring progress towards behavioural changes, including the short-term, medium term and long-term outcomes identified in VWC’s pathways of change for key target groups.[iv] These include the documentation of case study evidence on the following, among others:[v]

- significant changes in clients’ lives;

- women’s experiences with the Family Protection Act (FPA), including access to Family Protection Orders under the FPA; and

- outcomes from court cases related to interventions by the VWC Network.

Case studies are documented monthly by some VWC staff and Branch Project Officers, drawing on the total counselling caseload of the previous month, and submitted with monthly reports. Although the selection is not random, staff have been trained and mentored to select cases according to several criteria and guidelines outlined in VWC’s monitoring and evaluation plan.

At least one case study per month is required by most staff on the monitoring and evaluation team, although some submit more, and others may write up case studies during or immediately after 6-monthly reflection workshops to document examples of important trends in positive changes and challenges that have emerged over the reporting period, and that have been highlighted and discussed extensively during the workshop. The reflection workshops are also used to explore and verify whether examples documented in the previous 6 months are isolated examples, or whether they are indicative of broader provincial and national trends that require discussion, analysis, verification and action.

In summary, while case studies in all the categories above are written to assist with analysing positive outcomes on VWC’s pathways of change, writers have been trained to ensure they also select negative and unexpected outcomes. Challenges to achieving change, breakthroughs in dealing with ever-present obstacles, and the effectiveness of strategies are also explicit criteria for selection and documentation.

For example, for case studies on significant changes in clients’ lives, the guidelines instruct writers to document small steps taken by clients which may not seem to be significant to an outsider (or which may even be interpreted by some as negative), but which are seen as positive and significant by the women themselves, including why they are perceived in this way by survivors. The guidelines include prompts to: document the challenges that clients and Counsellors face in bringing about sustained change; identify how (and whether or not) VWC’s counselling, legal advocacy and community education/prevention strategies have assisted to bring about any change; and give equal weight to documenting case studies that demonstrate when clients have been able to step out of violent situations, as well as where they have not been able to do so. A similar set of criteria and guidelines are used for the case studies documenting women’s experiences with the FPA and legal outcomes.

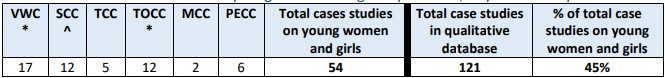

Age of the client or victim/survivor has never been a specific criteria for the documentation of case studies. Nevertheless, a significant proportion (45%) of case studies documented focus on young women and girls. The qualitative database used for this research includes all case studies related to young women and girls from across the country, written up by VWC and Branch staff from July 2016 through to May 2019 (Box 8). Most of the case studies were written in order to document evidence on significant changes in clients’ lives, and their experiences with the provisions of the FPA; a few related to outcomes from court cases.

Box 8: Database of case studies on young women and girls by location, July 2016 – May 2019

* Includes 5 case studies where young women were referred by CAVAWs (3 for TOCC and 2 for VWC).

^ Includes 2 case studies where clients were young women with disabilities.

4.2.3 Data analysis processes

A one-day data analysis workshop was held with 12 VWC staff in March 2019. This included senior counselling, legal, research, community education, management and other staff at VWC, as well as Branch Project Officers. Following a refresher on the methodology for the research, preliminary findings from both the quantitative and qualitative data were presented, and the strengths and limitations of the research (section 4.3) were discussed. Each research question was discussed in detail (Box 5 above). The analysis, interpretation and conclusions presented in sections 5 and 6 below is based on the reflections and discussions in the workshop. Follow-up meetings were also held with groups of key staff after the workshop to clarify points of interpretation and to ensure that valid conclusions were drawn from all data sources.

Each research question had several sub-questions for discussion in the March data analysis workshop. For the quantitative findings, these questions were designed to explore variations in the data by location, age group (girls under 18, and young women aged 18-24 and 25-29), type of presenting problem, and new clients compared with repeat counselling sessions; any surprises and trends in the quantitative findings were explored.

For the qualitative findings, additional sub-questions focused on 3 key topics for interpretation:

- whether the case studies provided accurate insights into the extent to which the needs of young women and girls are being adequately met by VWC Network services, or other service-providers, and whether any reliable conclusions could be drawn on these topics and on the impact of counselling approaches;

- whether we could draw any reliable conclusions about the impact of VWC’s community awareness and prevention activities in reaching out to young women; and

- whether the case studies overall are broadly representative of the severity of the various forms of violence experienced by young women and girls, or whether they tended to describe only a small proportion of the most severe types of cases seen during counselling.

The third question on the severity of violence was very important to ask, because when collated and compared over the 3 years, it was apparent that many case studies documented extreme types of physical, sexual and emotional violence and forms of coercive control, which by any accepted definition amount to torture – and because the severity of violence has never been a criteria for the selection of case studies. The firm conclusion of all staff at the workshop was that the database was typical and representative of the severity of cases seen weekly throughout the country by VWC Network staff.

In addition to the 4 key research questions, the last session of the workshop focused on the following:

- Overall, do the findings challenge or confirm any assumptions that VWC (or others) have had about the extent to which the VWC Network is assisting young women and girls?

- Are there any surprises, or other analysis needed about the types of violence experienced by young women and girls, the issues they are facing, how they are being supported, and their views about violence against women and girls? (This question was added to assist with identifying and prioritising future research by VWC.)

- Are there any types of violence experienced by girls and young women that are not captured adequately in the research data, or where young women are not approaching VWC for help, such as violence related to social media, and particularly image-based violence?

The analysis in this report also draws on several internal VWC reports.[vi] These documented key activities, milestones, and both quantitative and qualitative evidence of outcomes and impacts in the four years prior to the 2015/2016. These were used to test and validate interpretations and analysis from the March 2019 workshop, to ensure that all were soundly based on and supported by previous documented evidence and reliable sources, and to avoid confirmation bias. Further validation of the analysis and draft report was undertaken in a workshop meeting with 4 Port Vila staff held in September 2019, in a review by VWC staff in April 2020, and again in July 2020 following peer review comments.

Themes in the qualitative database are aggregated and presented as percentages in the analysis in chapter 5, using the relevant denominator (either the total research database of 54 or an explicit sub-set such as the number of women or girls). Quantification of the findings from the case studies is used to ensure that the findings are transparent. This approach was chosen to facilitate accurate analysis and triangulation with interpretations made during the workshop, and the data documented in the internal reports noted above.

4.3 Strengths and limitations of the research method

The research has several strengths and limitations. One strength is the reliability of the quantitative data, which is based on careful review of counsellors’ weekly data collection sheets, and cross-checking of the data where age was missing. The database includes all the delivery modes for counselling, including at centres, by phone and through mobile counselling in urban settlements, rural areas and outer islands.

Another strength is the one-day analysis workshop and the participatory process used to interpret and make sense of the findings. A third strength is that interpretations in the workshop were supplemented and validated by previously documented evidence in VWC internal reports to its funding agency, rather relying on memory, and by several further meetings between the author and key staff to ensure that findings were interpreted accurately.

One limitation of the research method is that no quantitative data has been used from CAVAWs (section 4.2.1), which means that it is not possible to know with any certainty whether girls and young women are accessing CAVAW counselling services to the same extent as the rest of the VWC Network. However, it is important to note that complex cases are referred by CAVAWs to VWC and the branches for counselling and follow-up actions, and 9% of the qualitative database includes such examples. Although CAVAWs are trained annually in basic counselling skills, many are only able to provide a referral service to VWC and the Branches, and their community awareness and prevention activities remains the most important part of their work. Consequently, this limitation is offset by the fact that these referred CAVAW cases are incorporated into VWC and branch quantitative data; the inclusion of branch data is a key strength of the research method which ensures that the data presented is national, including remote rural areas and islands from all provinces of Vanuatu.

Another limitation of the research is that only internal VWC Network data could be used due to financial constraints.[vii] Consequently, it was not possible to undertake interviews with young women’s leaders or to hold focus group discussions prior to publication to explore their views.

The strengths and weaknesses of qualitative and participatory methods of enquiry and analysis have been well-documented. Some potential risks include: the lack of a large or representative sample; poor facilitation; and confirmation bias, including over-generalisation of findings and over-reliance on striking quotes or outliers which may exemplify exceptions rather than trends.[viii] The qualitative database is assumed to be broadly representative of the national caseload, given the guidelines used for internal monitoring and evaluation purposes and the regular collection of case study material; this is reinforced by participatory discussion and enquiry during 6-monthly reflection workshops. Nevertheless, it is possible that positive outcomes are over-represented in the case studies in any one year, compared with the challenges faced in bringing about change. This risk has been addressed by drawing on the total database of case studies over 3 years, by supplementing the analysis with previously documented evidence in VWC internal reports, by quantifying the qualitative findings for transparency and to avoid confirmation bias, and by follow-up meetings with key staff to ensure that themes were interpreted accurately.

A final limitation is the fact that the quantitative data is only for one financial year, which constrains making firm conclusions about trends in access to services. However, although the qualitative database draws on a different time period, this is seen as a strength; combining the two data collection methods over different time periods provides insight into young women’s experiences since 2015/2016, adds a richness to the data and analysis, and addresses several of the potential limitations discussed above.

[i] The year July 2015 – June 2016 was the fourth and final year of VWC’s last funding phase with the Australian Government; a new funding phase commenced in July 2016. The original intention was to compare findings with a year in the current funding phase, which ends in June 2021.

[ii] Definitions in the text box are adapted from the following: VWC 2016 “Vanuatu Women’s Centre Program Design Document, July 2016 – June 2021”: 31; Carmody, M., Evans, S., Krogh, C., Flood, M., Heenan, M., and Ovenden, G. 2009 Framing best practice: National Standards for the primary prevention of sexual assault through education, National Sexual Assault Prevention Education Project for NASASV, University of Western Sydney; and Our Watch 2015, Change the Story: A shared framework for the primary prevention of violence against women and their children in Australia, Our Watch, VicHealth and ANROWS.

[iii] VWC’s counselling services are provided to women of all ages, and to girls and boys under 18 years. The VWC Network provides information services to men and women and girls and boys regardless of age, but no counselling is offered to men 18 years and over.

[iv] VWC 2017 “Vanuatu Women’s Centre Monitoring and Evaluation Plan: Program Against Violence Against Women, July 2016 – June 2021”, VWC, Port Vila.

[v] Other qualitative indicators in VWC’s M&E plan include: initiatives taken by community leaders and members to prevent and address violence against women and children and promote equal rights; outcomes relating to the involvement of male advocates trained by VWC and their engagement in VWC, Branch and CAVAW prevention and response activities; evidence of changes in policies, law reform, protocols and actions from VWC Network partnerships with government and non-government agencies; and several related to staff capacity building.

[vi] These include annual VWC Progress Reports to the Australian Government Aid Program from 2012 to 2016, and VWC 2016 “Activity Completion Report July 2012 – June 2016”, where evidence of key milestones and quantitative and qualitative outcomes was consolidated for the previous 4 years.

[vii] VWC has had aspirations to undertake larger and more in-depth qualitative research projects including the collection of data from primary sources since the national prevalence study was published in 2011. However with limited finances from donors, VWC had to prioritise the delivery of counselling and community awareness/prevention services over undertaking further research projects and consequently has only been able to undertake research using internal data sources.

[viii] For examples of the risks and ways to address them, including the rationale for a “qual-quant” approach (which quantifies selected sets of qualitative data) see Chambers, Robert and Linda Mayoux 2003 “Reversing the Paradigm: Quantification and Participatory Methods”, Paper submitted to the EDIAIS Conference on “New Directions in Impact Assessment for Development”, University of Manchester, United Kingdom (UK), https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247406698_Reversing_the_Paradigm_Quantification_and_Participatory_Methods , accessed 17 July 2020; and Chambers, Robert 2001 “Qualitative Approaches: Self Criticism and What Can Be Gained from Quantitative Approaches” in Ravi Kanbur (ed.) 2001 Qual-Quant – Qualitative and Quantitative Poverty Appraisal: Complementarities, Tensions and the Way Forward, Contributions to A Workshop Held At Cornell University, March 15-16, 2001, http://publications.dyson.cornell.edu/research/researchpdf/wp/2001/Cornell_Dyson_wp0105.pdf , accessed 17 July 2020. Note that quantification of the qualitative findings in this report is not intended to imply that they could or should be analysed statistically, given the small sample size and their collection for monitoring and evaluation purposes.